Kinnon Ross MacKinnon

June 18, 2015, 8:39 p.m.

With the queer high holiday of Pride season just around the corner, I am thinking about the importance of fostering positive body image for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer (LGBTQ) persons, of all shapes and sizes. So why would the subject of positive body image be a timely conversation as we approach Toronto Pride (June 19-28, 2015)? Well, being a part of the community myself, one of the observations I have made over the years is the number of LGBTQ-identified individuals who engage in 'Pride dieting' That is, in the months leading up to the annual big-Church-Street-dance-party, many LGBTQ folks begin to obsess about calories, carbs and abs, in anticipation of the event commemorating 'gay liberation'.

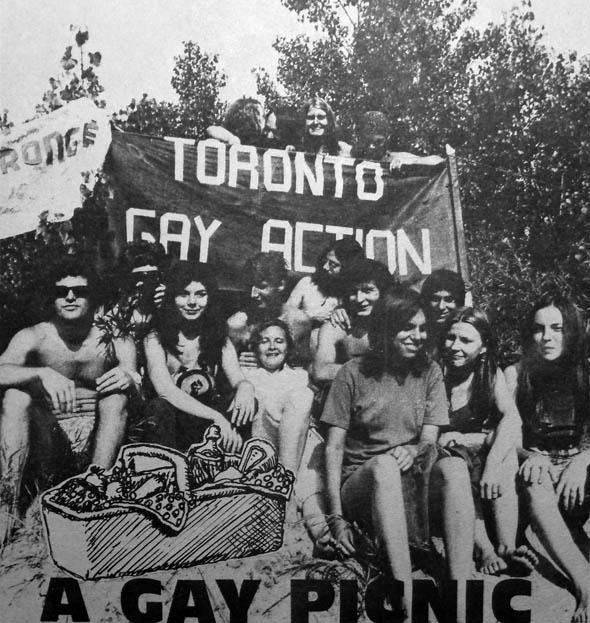

It is interesting to note that Canada's largest Pride event, Toronto Pride, began as a series of picnics in the 1970s at Hanlan's Point and Ward's Island. Queer and trans activists shared meals together over discussions of human rights, in order to take a stand against the discrimination based on sexuality that was being widely felt by Canadian sexual and gender minorities. This historical advocacy event contrasts starkly with the Toronto Pride we know today - the opulent corporate floats populated with slender drag queens, muscular jock-hunks, skinny twinks, lean baby dykes and ripped leather daddies. Some of whom are contracted out for profit, particularly for their looks, by entertainment companies. Since its grassroots beginnings, Toronto Pride has moved downtown, grown exponentially in size, and has largely shifted its primary focus from a political movement to a large street celebration.

While Pride festivities encourage us to be proud of our various sexual and gender identities, many LGBTQ people have been taught to be ashamed of non-normative sexual desires, gender expressions and body sizes or shapes. Thus, sexual and gender minorities develop shame after years of absorbing messages which suggest that queer and trans ways of living are inherently defective. And of course, the connection between feeling shame and the subsequent development of a poor body image has been well-established in the field of eating disorders.

Even outside of Pride season, LGBTQ populations have higher rates of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders in comparison to heterosexual and cisgender* groups. For instance, gay and bi men may be 6-9 times more likely to develop an eating disorder than straight men (Feldman & Meyer, 2007). Trans men and women also report a high degree of restrained eating and body dissatisfaction (Vocks, 2009). And while lesbian and bi women have a higher chance of being overweight when compared to heterosexual women (Yancey et al, 2003), they are also more likely to develop an eating disorder (Koh & Ross, 2006).

I am not implying that there are biological factors that determine sexual and gender minorities' body image outcomes. Instead, it is likely that the experience of living within a homo/bi/transphobic culture, and the constant hum of anti-fat stigma circulating LGBTQ communities, creates an environment which nurtures issues around body image, weight, and shape. Experiencing social isolation, rejection from family, and discrimination in work places, schools, and healthcare settings is tough. Sometimes individuals deal with such stigma and stress through the body – coping by adopting specific food rituals and/or obsessive exercise regimes. Of course, being rejected by romantic or sexual partners on the basis of size or shape certainly does not help someone develop a healthy relationship to their body. Log into popular gay dating apps, Grindr or Scruff, and browse a few user accounts – it will not take long to observe a fat-shaming profile. A similar message is promoted by the types of lean muscular bodies chosen to be displayed atop Pride parade floats every year. The pressure to look “perfect” in order to be valued as sexually desirable is immense, and may lead to increased body image issues and eating disorders within LGBTQ communities.

So, as we come into Pride season, I urge LGBTQ communities to re-examine the practice of pride dieting, and the use of anti-fat language which has the consequence of shaming those who cannot, or refuse to attain, the near-“perfect” body types often displayed upon our parade floats.

Image Credit: http://www.clga.ca/photographs

* denoting or relating to a person whose self-identity conforms with the gender that corresponds to their biological sex; not transgender

Kinnon Ross MacKinnon is a doctoral student at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto and studies LGBTQ health equity issues. He is also a member of the Re:Searching for LGBTQ Health research group. Kinnon has presented at NEDIC's Body Image and Self-Esteem conferences and is a former facilitator of the Men's Body Image Support Group offered by Sheena's Place in Toronto.

Feb. 4, 2018, 6:24 p.m.