Andrea LaMarre

July 25, 2019, 1:48 p.m.

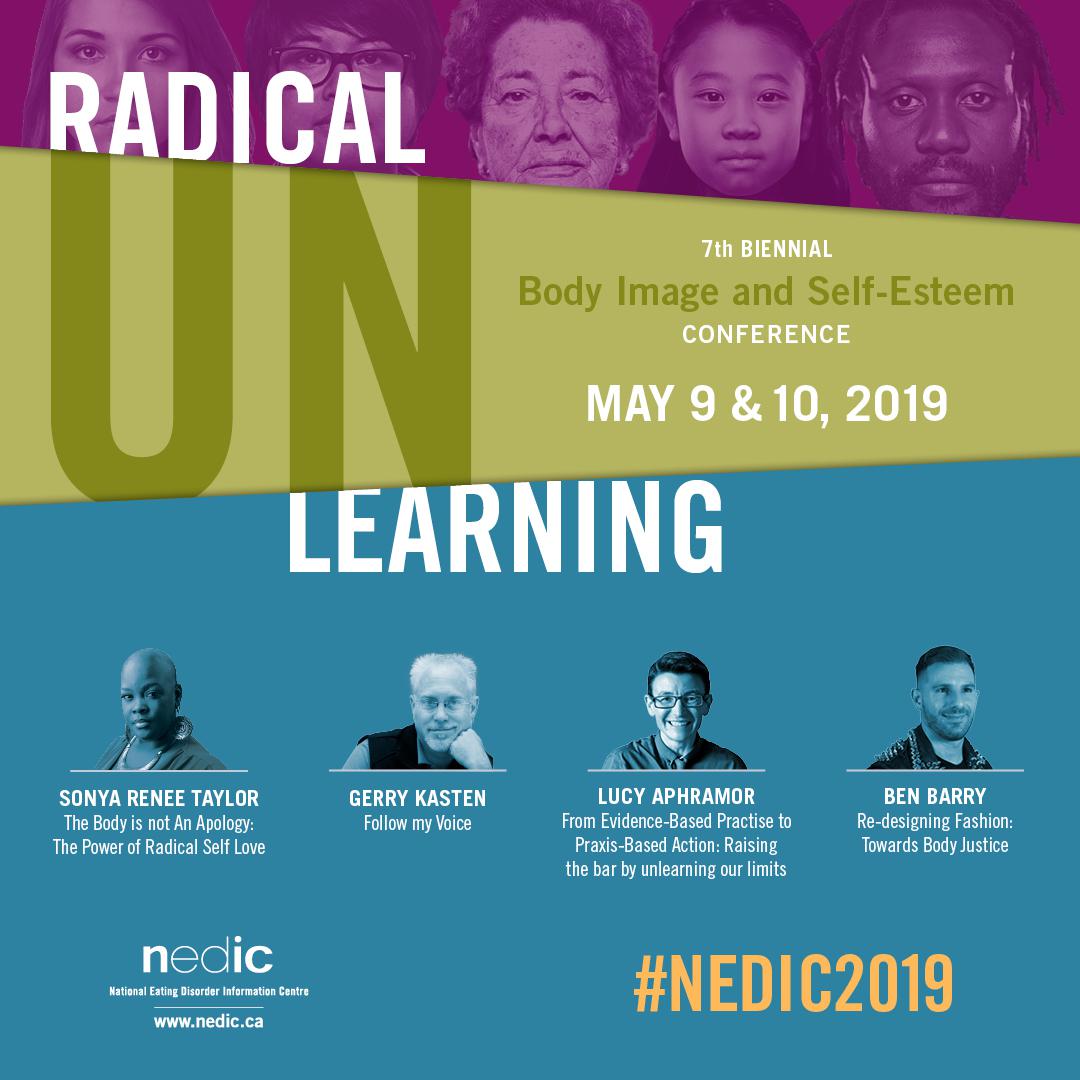

I look forward to the NEDIC conference every two years. In my experience, NEDIC takes seriously some issues in the eating disorder field that get less airtime at other gatherings like it. Topics covered at the conference regularly include:

- Ways of making eating disorder treatment more accessible to those who do not always get access (think people who are marginalized along any number of lines, including race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and more)

- Looking at different healing modalities, like artful and compassionate approaches to treatment that might hold promise

- Challenging weight stigma

- Therapist, researcher, and advocate self-reflection, and encouragement to name and challenge internal biases

Speakers are engaging and engaged in the process of questioning dominant ways of doing, being, and seeing in the eating disorders field. This is a step toward the radical unlearning the conference asked of us in its theme this year. And as keynote speaker Sonya Renee Taylor reminded us, the process of radical unlearning is uncomfortable, and requires that we look critically at our own thoughts and actions. During Sonya’s keynote, I found myself deeply feeling the messages she shared, especially the way that white supremacy shows up in conference spaces--and, as a white person, in myself.

The words “white supremacy” can provoke a reaction, to be sure. That reaction, that feeling that comes up in your gut (or maybe it is someplace else for you), isn’t something to stuff down--it is something to feel. I could be over-generalizing, but I think that we all like to feel like we are good people--nice people. But as Sonya said:

And bravery is the spirit of this post, and, in my experience, of NEDIC’s response to the things that come up when we get together and tackle challenging topics. Before we move forward together, we need to look inside and look at how, indeed, white supremacy and a politics of niceness has shaped and continued to shape the spaces we create. When we do this, it might hurt. As a white person, a cis-gender, heterosexual, thin, and passing as able-bodied person, it is my responsibility to deal with this discomfort in ways that do not centre my experiences. I do this imperfectly--maybe you do, too. One of the things I considered before I began writing this post was what my role is as someone who tries to engage in allyship (which is a verb, something that involves action) in reflecting on what I thought about a conference where my experience is easily centered. I know that even being at a conference reflects layers of privilege; standing up on a stage and having people listen to me is a familiar experience to me; I can attend conferences because I can pay for them and I have flexible employment that enables me to work from anywhere. As I continue my work, I am increasingly interested in stepping to the side and hearing from others’ lived, embodied expertise. So I wondered: who am I to reflect on what went well, and what could be improved?

I write these things not to discredit myself but to invite us to collectively consider that though I regularly work in partnership, I will not have all the “social justice answers,” and I shouldn’t, either. If my reflection serves no other purpose, it will hopefully serve to invite others who are similarly privileged to think about micro- and macro-level work that we can do to create the conditions in which it will be safe for varied experiences and stories to be told. A lot of my reflections are my take on things that I’ve discussed with wonderful, generous colleagues, including at the conference itself. The critiques are things I’m actively working to unlearn. What do you need to unlearn?

As is likely evident by now, Sonya Renee Taylor’s keynote talk was a highlight of the conference for me, and, I gather from Twitter, for many others. One of my favourite things about her talk was how Sonya centred the experiences of many; she drew on the collective expertise of those who have been harmed by the eating disorder treatment, research, and advocacy status quo. She invited us all to consider how fatphobia, ableism, racism, and other biases impact the work we do. She shared quotes from those who longed for an eating disorder treatment system that does not prescribe eating disordered behaviours to those whose bodies are read as “too big.” She encouraged us to ask about our motivations for and experiences of doing this work, or in her words:

In her talk, Sonya entangled the body and eating disorders with social, political, and economic structures that maintain inequities. For example, ongoing settler colonialism alienates people from traditional foods and food structures, making eating fraught for many marginalized folks. The pursuit of “health,” normatively and narrowly defined, reproduces ableism as it asks everyone to aim for one singular standard of bodily “achievement.” Even when size diversity is taken into account, there is often an imperative to “be healthy”--which automatically excludes many disabled people. Importantly, Sonya’s talk empowered each of us to start with ourselves, but not to stop there. Yes, it is important to develop self-compassion and critical to establish self-forgiveness when we inevitably fail to show up in a way that challenges existing problematic systems. But it is not enough--we need to dismantle existing structures that keep people small.

Another highlight for me was Ben Barry’s keynote, which brought the fashion conversation to the fore. Ben highlighted how fashion cycles have been built on narrow norms for bodies that are reproduced in fashion education. Students learn how to dress only some bodies--thin bodies. From starting his own modelling agency with a much broader array of bodies when he was 14 to fundamentally shifting the way fashion education is taught, Ben has been working collaboratively to make major change in the fashion industry. His talk included references to some amazing work that invites fashion students and designers to actually engage with the needs and desires of people who wear clothing. He shared some inspiring examples of change, including work by Deborah Christel on fat fashion pedagogy, Grace Jun on disability fashion, and Kelly Reddy-Best on a black lives matter fashion course, among others. Ben’s keynote was inspiring in offering ways forward that move beyond simply sanctioning the use of thin runway models and reaches back toward the roots of body exclusive approaches to fashion.

Other sessions I attended offered ways of being more expansive in eating disorder practice, including a session on integrating intuitive eating into eating disorder recovery (with Shawna Melbourn, Dina Skaff, and Josee Sovinsky), and on art therapy to break through barriers that exist in the eating disorders field for marginalized people (with Marbella Carlos).

I also had the good fortune of presenting about radical trust in eating disorders with Carmen Cool. We had a fantastic and engaged audience, and collectively asked questions about why it is so hard to trust people with eating disorders, how we can value lived experience as expertise, and how to move through the challenges of trusting our own bodies and those of others. Our session brought up a lot of emotions and vulnerability, including for me. And, as often happens, the session also brought misunderstandings and harm into the room, which brings me to…

I have yet to run a session at an eating disorder conference about weight stigma and other aspects of marginalization where at least one person has not questioned the use of the word “fat” as a descriptor. This conference was no different. In discussing a case study, tensions surfaced around the word “fat,” and it is worth unpacking how and why this comes up so frequently, the harm that these discussions can cause, and how to move forward together to prevent future harms.

Negative reactions against the word “fat” as descriptor often (but not always) come from people who exist in smaller bodies. Questions I’ve had include: “I encourage my clients not to use the word fat, because they are putting themselves down when they call themselves fat, so why are you using it to describe people?” or “I don’t think people in the Health at Every Size/body positivity/size acceptance/eating disorders field would appreciate you calling people fat, so can you please not do that?” and even “we don’t say that people are cancer or diabetes, we say that they have those things.”

I think it’s important to be clear that when we--when I, as a thin person--use the word fat in these contexts, I am drawing on the word that many people use to describe themselves in a neutral or positive way. It is not up to me to define someone’s body size. It is not up to me to tell someone how to refer to their own body. Not everyone wants to use the word fat to describe their bodies--and that is ok, too. However, many fat activists have reclaimed the word fat, which has been used to harm in the past (see this interview with Sophie Hagen or more on why it is important to reclaim the word fat). In its nature, the word fat is not inherently bad. When we react to its use in a way that shuts down people who use it to describe themselves, we are saying that there is something wrong with being fat, which there is not. It is important to note that I am not the first person to explain this, and I regularly learn from fat colleagues who do amazing work. Among fantastic explainers, this post by Your Fat Friend explains the issue; Marie Southard Ospina describes moving beyond “fat as insult” in this piece; and Angela Meadows and Sigrun Danielsdottir wrote an academic article about fat language.

The last question listed above (where we “aren’t *insert medical condition here*) is worth unpacking as well, and links to broader stigmas around fatness. Not too long ago, "obesity" was deemed a chronic disease; a medically-definable condition. Some even propose using person-first language in an effort to de-stigmatize “obesity,” not recognizing that this can in fact reinforce stigma by calling bodies a problem and making the assumption that there is a “cure” for a body size. In reality, our body weight is less modifiable than we would be led to believe; bodies come in a variety of shapes and sizes, and diversity is natural. No amount of prescribing dieting and excessive exercise is going to shift all bodies into some miraculous middle ground of perfection; more likely, this will result in bodily disconnection and disordered eating.

I would love to see a day where people were able to move beyond fearing not only fat itself but the word fat. I understand the tension that can come up when moving beyond the way that we have been taught to use--and fear--the word. This comes back, yet again, to Sonya Renee Taylor’s talk, in which she reminded us that we are all steeped in the tea of society. Admitting that we have biases is a first step toward challenging them. I would invite each of us to enter into conference spaces thinking about how our bodies exist in relation to those of others; not to apologize for our bodies, but rather to do the work Sonya and others make so clear that we need to do.

Whenever I go to a conference, I try to think about who is not in the room. Conference spaces are still not accessible to all, for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to cost, physical access, and emotional access. This is not a critique unique to NEDIC; it is a tale as old as time. People may not feel welcome in conference spaces, from which they have been historically barred. Structures that bar people from participation go back far beyond the registration desk; they stretch back to differences in educational access along racist and ableist lines. They manifest in ways that have become largely unconscious. I am not the first to raise these questions; one example is this piece in the Guardian about the inaccessibility of conferences for disabled academics. Many others have raised concerns about the way that in order to “get ahead” in many fields we are all expected to attend conferences and network, and yet doing so can be a financial, emotional, and physical drain. This is to say nothing of the micro and macro aggressions faced by those who do not fit the white, cis, able-bodied, and thin expectations for bodies in public spaces.

So what can be done to increase access, at conferences? Amazing disability, LGBTQ+, BIPOC, weight stigma, and other (and all of the intersections of these!) scholars and activists have taught me a lot about accessibility. Among others,

following Annie Segarra on Twitter and Youtube and Mia Mingus on Twitter has been life changing, as has engaging with folks from Tangled Art + Disability and Creative Users Project and learning about Sins Invalid during my work with the ReVision Centre has helped me to consider levels of access and layers of privilege in all sorts of spaces. At the NEDIC conference, several conference attendees, and Lee Thomas in particular, provided significant labour in thinking about accessibility via Twitter and in conversation. I have also learned a tonne about accessibility in the eating disorder space over the years at NEDIC and elsewhere from Kaley Roosen (with whom I presented at NEDIC 2017). These people and groups are among many who I know I can always learn from when it comes to access and inclusion.

In the conference context, access can look like a number of things, including but certainly not limited to:

One way of thinking through these aspects of access is to create an access guide. A recent example of what this can look like is from the Cripping the Arts Symposium in Toronto. More examples of accessible conference planning are available here and here, and remember that access goes beyond reading policy--talking to (and compensating) disability scholars, BIPOC advisors, LGBTQ+ and fat scholars and activists (and those who live at the intersections of those, and beyond!) is a critical part of making our spaces truly open. If we want to get radical, we have to put in the work. NEDIC as an organization is open to feedback, and has demonstrated a desire to learn and change; there is a great foundation to build on and grow together. One example of moving toward access is that NEDIC had a therapy dog at their conference, which was a wonderful gesture. They also encouraged microphone use, though technical issues made this challenging to enact, and were very available for feedback and adjustments throughout the conference.

NEDIC is making inroads into a space that can be very inaccessible, very limited in terms of representation, and very narrow in view. To a certain extent, a conference is only what it can be; a space to share and exchange ideas. Often the strength of the feelings and ideas brought up at a conference only hold us over for a short period of time, until we are back in our own worlds, our own daily struggles. Maybe to be truly radical, we need to do away with the conference structure as a whole, and find other ways of connecting for change. For now, however, we have conferences as a place and a moment of intentional connection. Building on this momentum, let’s think about how we can enact accessibility in the eating disorders field. Let’s unlearn the narrative that doing this is “too nit-picky” or “too hard.” It isn’t. It’s necessary.